period of service

When I took command of Charlie Company on Fire Support Base Granite, after the ground attack, I sensed a mood I had never seen before in the Vietnam War. It was a mood of defeat and fear. I immediately vowed to not move this unit back to Camp Evans for any length of time, until the unit jelled and once again came together. I was concerned that some of these men actually thought a five foot tall, eighty pound Vietnamese communist was superior to them on the battlefield in these mountains. This was especially evident when I announced we were walking off the fire base instead of choppering out as the sun went down. ‘What do we do if we meet the NVA, Zippo?’ I just said: ‘Kill them.’ My attitude appeared foreign to anything they had heard lately and they were not the happiest of campers that day.

After some false starts and some indecision at the battalion headquarters as to who commanded the company, I moved with the radio operators (RTO’s) up to the point element and moved ou t. This would not be the last time I found the situation required this type of leadership. But I began to see a gleam return to the eyes of these good American soldiers. I knew it well and I was sure it would permeate once again a group of soldiers I would lead in combat. But at that point even I had no idea they would shrug off defeat and very soon become what the command described as the 'finest rifle company in Vietnam.’ By the next day, when we prepared to return to Camp Evans for a day, I knew they were mine.

t. This would not be the last time I found the situation required this type of leadership. But I began to see a gleam return to the eyes of these good American soldiers. I knew it well and I was sure it would permeate once again a group of soldiers I would lead in combat. But at that point even I had no idea they would shrug off defeat and very soon become what the command described as the 'finest rifle company in Vietnam.’ By the next day, when we prepared to return to Camp Evans for a day, I knew they were mine.

What had struck me since my assignment to the 101st Airborne was a leadership environment foreign to me. Though very superior to what I had observed in the 1st Cavalry Division in 1969 during combined operations with my Vietnamese Rangers, in this famed unit, I found a vast gulf between officers and senior NCO’s and the junior NCO’s and the men they were assigned to lead. These experiences in 1969-70 stood in stark contrast to my experiences in Special Forces and the First Infantry Division during the 1965-68 time frame. Rather than a desire to win, I sensed at higher levels of command a desire to limit casualties and at lower levels to merely survive and go home. This was coupled in the 1st Cavalry with a seeming general acceptance of drug use and a tendency in the Screaming Eagles to basically ignore it as much as possible. I was determined to take neither of these courses in C company and became an almost country preacher to enforce a zero tolerance for drugs. In the field we became very nearly a one hundred percent drug free company and in the rear, peer pressure from within the ranks would nearly eliminate it there. Then the truly important leadership challenge had to be met; how to instill a desire to win and a thirst for the challenge of the fight itself?

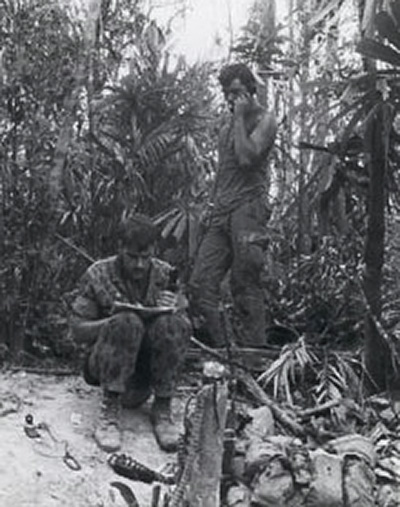

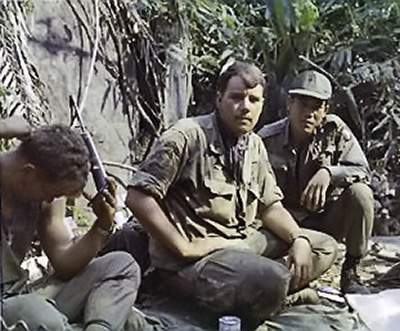

I started with eliminating the forced separation within the ranks, resulting from Army instituted programs meant to curry favor with specific groups and races. When confronted with legions of black soldiers who all held shaving profiles, I banned shaving for all soldiers in the field. The soldiers might not have been pretty but by God they all looked the same. Then I made use of the same logic in the rear area. Every soldier would have a clean uniform and be shorn in a military manner in the rear area. Captain Higgins and First Sergeant Rollins would have a barber standing by. After black soldiers went through the buttery goop and ‘butter knife’ routine a couple times they resumed normal shaving and became an integral part of the fighting unit. One of the greatest assets available to me was staff sergeant Ronald Marks (nicknamed REMARKS), a former Ohio State football player who happened to be black . He maintained a constant chatter about how things had to be and that what happened 'in the world (USA)' had no bearing on how we operated in the war. The 1/506th year book shows the result in the unit pictures for each rifle company. Among the hatless, long haired and shirtless individuals from other units are the platoons of Charlie Company looking like soldiers and standing straight, proud and tall. We engineered everything from a company club to barbeques to isolate the soldiers from other units as much as possible (we identified much of the revolutionary fervor and drug use being generated out of the very club system designed to build morale. The men of C Company took on a much needed pride, confidence and yes a certain arrogance. They clung to one another as different and better than all others. They developed a certain swagger based on a belief they were the very best. Any general or colonel landing in the jungle and put off by their multi-colored uniforms and lack of a shave could not in good conscience argue with the results - dead enemy soldiers lying there for all to see. When a question developed on the staff if Charlie was really killing as many enemy as they claimed, I had the next batch slung in a net, under a helicopter, then deposited on the Currahee pad, in front of the TOC for all to see.

. He maintained a constant chatter about how things had to be and that what happened 'in the world (USA)' had no bearing on how we operated in the war. The 1/506th year book shows the result in the unit pictures for each rifle company. Among the hatless, long haired and shirtless individuals from other units are the platoons of Charlie Company looking like soldiers and standing straight, proud and tall. We engineered everything from a company club to barbeques to isolate the soldiers from other units as much as possible (we identified much of the revolutionary fervor and drug use being generated out of the very club system designed to build morale. The men of C Company took on a much needed pride, confidence and yes a certain arrogance. They clung to one another as different and better than all others. They developed a certain swagger based on a belief they were the very best. Any general or colonel landing in the jungle and put off by their multi-colored uniforms and lack of a shave could not in good conscience argue with the results - dead enemy soldiers lying there for all to see. When a question developed on the staff if Charlie was really killing as many enemy as they claimed, I had the next batch slung in a net, under a helicopter, then deposited on the Currahee pad, in front of the TOC for all to see.

The relationships with senior commanders were generally good and little understood by outsiders. LTC Dave Pinney was a Special Forces officer and we had common ground to walk together. LTC Bobby Porter was a former MACV adviser and seemed always to sense how things were actually going and not how the staff above was reading the intelligence. He just flat loved Charlie Company. LTC Hugh Holt's and my relationship would never be understood, in its true meaning, by anyone listening to a personal or radio conversation between us. He was a good and decent man who operated too many times out of 'feelings' he had while studying a map or from a briefing he had received. I learned to 'just say no' a long time before Nancy Reagan coined the phrase in her campaign against drugs in the eighties. LTC Holt would call in the middle of the night with Charlie Company dug in up to its eyes and LP’s and ambushes out. 'Zippo, this is Checkmate, I want you to think about moving one hundred and fifty meters east of your position as I have a feeling you will be hit. Give me your response to this order - over.' 'Checkmate, my response in a word, NO!’ Usually this ended the conversation but there were times when he was getting pressure from above and insisted on arguing the point. Finally I would say, ‘Stalemate, this is Zippo.’ I am dug in with a fire plan and if I am going to get hit I want it to be here and in fact I hope the sons of Ho come here so I can kill them.’ That would end the discussion. I heard conversations over the net with Checkmate and Sullivan in Bravo Company and Spartan in Alpha Company being similar if not quite so pointed. The D Company Commander tried and was relieved and replaced by 'Ranger' Don Workman, the officer I had threatened to fire in Echo Company when he was the recon platoon Leader. He died when a helicopter he was trying to board fell upon him and the blade nearly decapitated him. He had all the attributes to be an outstanding commander but the command was pushing him beyond his capabilities and he died, taking a good portion of his company with him. Don’s fault? No way! The fault lay with those who were determined to make him a star before ready. In the messhall, when Major 'Wild Wes' Ford, the XO, tried to tell me what an outstanding commander 'Ranger' was, I simply said 'cut the crap, sir.’ ‘I will not sit here while you and the command spin myths to justify sending that lad to die along with his good men.' Battlefields dictate their own reality and no senior commander, medal citation or ceremony at Fort Benning or West Point will ever change the simple truth; they sent that lad out for themselves and not for his men or even himself. The command failed Ranger and his men. In Charlie Company we 'just said no' and continued to slay the enemy.

What struck me as most surprising upon taking command was not what this infantry company did in the jungle but all the things it did not do. The unit had been a bunch of 'ridge runners.’ They walked the trails along the ridges and rarely ventured into the crevices and ravines along the flanks. They not only did not dig in but put up poncho hooches at night. This lasted one night with me and I pointed out the ponchos of a sister company glistening in the sunlight on the next ridge. They looked like shining mirrors showing each position to our sly enemy. No more poncho hooches for C Company except on a fire base. They did not leave stay behind ambushes to net the cold and hungry NVA coming to dig through a smoldering trash sump, from the last night’s NDP, in those cold and misty mountains.

Starting in April 1970 when Charlie Company began to kill the enemy, the brigade and division would send us to Eagle Beach for a three day R&R. I allowed each squad to design their individual uniforms from available patterns at the Eagle Beach tailor shop. As long as each squad member looked the same, I did not care. These ran from black fatigues to Korean spotted camouflage. All these things were meant to instill a unique spirit in an airborne unit populated by mostly leg personnel in 1970. It worked in spades. They became a cohesive unit which shunned all others as lesser men and soldiers.

When returning to the rear area from operations, other rifle companies would shuffle in one’s and two’s from the chopper pad back to their company. Without a word of direction from me, Charlie Company would all wait at the side of the pad until I got off the last bird in. Then they assembled behind me, beards, multi-colored uniforms and all. Then with what LTC Bobby Porter would come to describe as the 'Charlie Company stroll,’ they would swagger to the company area as a unit, ignoring all others as lesser men. After April 1970 other units would gather along the road to watch us silently pass by. We had earned the respect of our peers. The fears surrounding Granite faded into memory and were replaced with a determination to never again be caught unaware. A day or night never passed when ambushes and LP’s were not posted. No sniper team would ever be deployed at night on ambush or LP. They did their vital duty at a level and visibility which gave them the advantage. Charlie Company morphed into what others called 'Zippo's Zombies’ and what the troops in the company called 'Zippo's NVA Hunting Club.'

The artillery forward observer (FO), 'Chicken-man' (based on the character on AFVN by that name and not on his courage, which he possessed in spades), his arty recon sergeant and RTO called 'Short-round,' based on his just over five foot stature, were always within arm’s reach. They became an integral part of the company headquarters along with three primary RTO’s: 'Spud,’ Big Ed Miller, Chief (a veteran of the Big Red One), and 'Rookie,’ a young FO from the 4.2 Inch Mortar Platoon in E Company (who came one day and I just never gave him back). All joined in the battle to get real tube artillery support in the face of the ammunition supply rate (ASR )imposed since the destruction of the huge ammo dump in Long Binh in 1967 by sappers (this was officially denied but I was there with the 2/28th Infantry of the Big Red One when they blew it. What angered us were the ever present harassing and interdiction (H&I) fires which rarely hit anything but did not seem to be limited by the ASR. A constant battle was fought about getting useful marching fires or recon by fire on suspect enemy locations. Finally a short meeting on an LZ, with MG Wright and the brigade commander settled this once and for all. ‘Give me the artillery, General, and I will give you broken and dead NVA and not craters and broken tree branches.’ They removed the fetters for C Company and we were able to operate with guaranteed support.

The same was true for ARA (Dragon Gunships) and our own personal flying point-man and flank/rear security warrior, the brave OH-6 pilot known as 'Squirrel,' who flew into battle with a silk scarf tied to his leg and once snatched a mortar firing at us near a deserted fire-base with a grappling hook lowered by his gunner. Later all these things would come together with Charlie catching a large special unit making a tactical mistake and whacking them good but that was later.

The company was patrolling, the new men were learning and then the terrible, wet day came when an error in leadership cost us two of our best. But we did not know this yet in the first weeks of April.

Our need for instant support and for circling commanders to stay out of our artillery support fan was reinforced by our sitting just off a deserted firebase and observing the opposite ridgeline from concealed positions. Fido Martin’s platoon was sent toward the river and we watched for movement of the enemy getting out of his way. Then in broad daylight the lead elements of an estimated enemy Sapper Battalion made a fatal error which would result in the area to be known after that as 'Zippo's grave yard.’ An NVA made a dash across a small LZ, soon to be followed by a stream of others as we sat observing. ‘Sir Charles you have just made a costly error, be prepared to fry.’ As happens so often in war, he who takes shortcuts will die. As SSG Steve Smith maneuvered, we brought in artillery, gunships and eventually TAC-AIR and hammered one sapper battalion so ferociously that they dropped weapons, rucksacks full of satchel charges, an 82mm mortar base plate, and one RPD machine gun and tried to flee, dragging their wounded with them. Their total ability to respond was two RPG rounds and a couple bursts of automatic weapons fire before they were hammered into oblivion.

BATTERY SIX,THREE BY THREE (Basically six rounds from each gun in the battery of six guns fired along all four sides of a three hundred meter square for a total of one hundred and forty four rounds of HE and VT fuses mixed.

The size of the enemy unit was calculated by nearly forty rucksacks recovered with satchel charges. The one RPD MG and the 82mm mortar base plate denoted that the heavy weapons company of the battalion was present. Female compacts with rouge in two rucksacks and one gaffer’s hook for females to drag away bodies were also found. Thus two sapper companies and one support company/heavy weapons company were present. Two forty man sapper companies and one forty man/woman support company (heavy weapons and medical) = ONE NVA SAPPER BATTALION.

Raider led his platoon into the killing ground and recovered the communist equipment. The young airborne ranger was twenty years old. His platoon leader had left from Granite and never returned after the battle. From that day on I refused all offers of a replacement. 'Raider' had earned the right to lead his men in battle and remained the platoon leader until he was seriously wounded and medevac’d.

When I took over Charlie Company, we had two Senior NCO’s in the field in the line platoons. They were SFC Frank Foronda and SSG James Lockett. God himself could not have blessed us with two finer examples of NCO leadership in time of war. Then SSG Lockett died. A terrible mistake by his platoon leader was the driving force behind his death. As a former platoon sergeant I knew where the man in that position was supposed to be in the line of march during training or war. Lockett belonged at the rear of the column, ready to assume command if the platoon leader fell in combat. But the roles had been reversed without my knowledge and the ever loyal Lockett would never tell. Lockett was leading from the front when he fell along with Longmire that terrible day. The platoon leader was hanging back. Brave SSG Lockett fell and his platoon leader was fired. I had neither the time nor patience to train officers to lead. I could fine tune but I would not waste lives making up for what any officer training school had missed. The true reward for leaders was not a medal or glory but simply an opportunity to lead American men in a war that too many others seemed hesitant to win. It was not about 'command time' or what an officer needed for his career development and any officer assigned to me who stated that his motivation was his own 'need of a platoon' was sent packing back to battalion or was never assigned after talking to me. The equation for success in battle must be geared to providing the leadership needed by the men and not about officer career development. It is not a two-way street but a singular route to battlefield success and victory in war. Un fortunately the US Army did not correctly assess the situation in 1970 and too many times, officers who had lingered in training commands, staff jobs, Europe or in school were assigned because 'he has not had a command.’ An officer I threatened to fire in E Company was given command of a company after openly lobbying on the staff to have his predecessor relieved. Thus his assignment had nothing to do with battlefield needs. He was a fine young man but image meant more than truth to this youngster and he and too many men from his unit died in an attempt to help him achieve. The day he died he called me on my company internal frequency but and asked for help but some in the command felt this would 'steal his glory.' It was a needless loss of life.

fortunately the US Army did not correctly assess the situation in 1970 and too many times, officers who had lingered in training commands, staff jobs, Europe or in school were assigned because 'he has not had a command.’ An officer I threatened to fire in E Company was given command of a company after openly lobbying on the staff to have his predecessor relieved. Thus his assignment had nothing to do with battlefield needs. He was a fine young man but image meant more than truth to this youngster and he and too many men from his unit died in an attempt to help him achieve. The day he died he called me on my company internal frequency but and asked for help but some in the command felt this would 'steal his glory.' It was a needless loss of life.

Other than Captain Bill Higgins, the XO, I had one other officer who required no training and was born to be a leader. This officer was Special Forces qualified and brought an attention to detail and a determination to fight to the combat table. Lieutenant Martin led his men in battle and his nickname became 'FIDO' based on his response to those who complained or wimped out - 'F--k it, drive on.' The other platoon leader 'Peanut' was a young officer whose platoon closed around him until he became qualified to lead. This is how it must be in war as the least experienced must take command of much more seasoned warriors. Those whose egos will not allow this must be fired or they will get your men killed and/or die themselves. Within two weeks Charlie became set to do battle with the NVA in I Corps, personified by the 6th NVA Regiment who had become known as the 'Butchers of Hue' back in 1968. At the end of my tour, the killing of the commander or political officer of this infamous unit, by Charlie Company, would nearly cost me my career in a little understood incident. But at this time none of that was known. We were again sent to Eagle Beach for killing the sapper unit.

I never ceased to be amazed by things the troops in Charlie Company were able to achieve and the level of motivation they could maintain in the face of adversity, racial problems, fellow soldiers who at times refused to fight and in some cases to even board the choppers to go to fight. It was a myth that Charlie Company never had problems as other units did. We merely handled them as much as possible within the unit and once the troops started to win they were the greatest obstacle to anyone trying to cause a disruption or dissension. As I watched them hump all day and actually use every trick in the book to nail the enemy, I began to stop comparing them unfavorably with others I had led in battle. Soon every day as I watched them prepare to fight another day or to prepare to dig in for the night one singular thought seemed to consume me: ‘God I love these men like no others I have ever known.'

Then the day came when my decision to leave Raider in charge of 3rd Platoon proved to be the right decision but almost cost my baby-faced young airborne ranger staff sergeant his life. He reminded me so much of myself as a young NCO that there were days when I forgot he was not me. Whenever things got dicey I called for Raider as FIDO Martin and I both began to look at him as a potential officer. That this was at times unfair to Raider and his men was sometimes forgotten as I looked into those eager young eyes and once again sent him into the NVA den of evil, charging to the sound of the guns. Then he fell to enemy fire wounded and nearly lost his life but in the process created a war story recounted at every reunion.

As we moved one day with Raider's Platoon on point, there was a meeting engagement with NVA caught unaware by the quiet approach of the platoon. In the gunfight which ensued a bullet nearly ripped Raider's arm from his shoulder but he was back up and led his men until the enemy faded away into the jungle mists. Then I heard the shout as I moved forward: ‘Raider is hit.' We got to him and he had taken on that pallor I knew too well as the onset of shock. ‘Snap out of it Ranger, it isn’t that bad.' Yet in my own mind I knew if I did not get him out of there my good man was in deep trouble. I called for a medevac.

I just knew that once the dust-off was on station they could hoist my two wounded up into the bird and get them out to the hospital ship Repose. The greatest men in Vietnam, with the exception of infantrymen of course, were dust-off pilots and their brave crews but that day Dust Off 'TRIPLE NINER' was having a bad day and my favorite airborne ranger was wounded. I should have known something was amiss when the pilot asked, 'Is that LZ secure'? My main OH-6 pilot 'Squirrel‘ came on the net and read the Dust-Off the riot act: ‘Look pal there is no LZ and I and these gunships you brought with you will do our best to cover you while you hoist the wounded up.' Then he asked me if my mountainside PZ was 'secure.' I exploded; ‘In case you did not get the word pal, there are no totally secure places in this country but I and mine, along with your cobras and Squirrel will do our best to make you feel comfy. Now drop that jungle penetrator. He did drop the penetrator and just after my two soldiers had entered the uppermost branches of those tall mahogany trees, an NVA on another ridge fired on the dust-off. The pilot dropped the nose and dragged Raider and the other man through the branches until the cable snapped and they rode that yellow penetrator a hundred feet back to the ground, sitting down. That ride down would eventually cost Steve Smith a lost leg, bad back and probably a bad dream or two in later life. One thing was certain, the twenty year old hard-charging Airborne Ranger who went up on that penetrator came back down, at least for a moment as Mrs. Smith's little boy Steve: ‘Never mind, Zip, I can walk back to Evans. I am OK and I am not taking that ride again. ‘I just looked at him: ‘Shut up, Raider.'

I contacted LTC Porter 'Razorback' and we coordinated for the same pilot to get another bird and come back out. As he settled into a hover again he asked, if somewhat sheepishly, if the PZ was secure and I just directed him to look out his left window. ‘That young man with the M-60 Machine Gun is Harlan Wright from Harlan County, Kentucky and if you break this basket off or refuse to drop it to us, he will shoot you down. I heard Squirrel say, ‘Best listen, he will do it.’ And with a wide eyed Raider looking through the lattice of the basket as it made a swinging circle as it ascended, dust-off accomplished his mission. The only medevac who ever showed less than absolute courage redeemed himself within an hour and saved two lives. 'Zippo, sorry about that first pass.' I felt charity: ‘Go and sin no more.' He flew for us and around us after that, risking his life to save others, never ever again hesitating or dragging troops through the trees. He redeemed himself in spades and we never saw Raider again until we started having reunions a few years ago. I missed him every day, personally and professionally. His father a serving naval officer sent me a thank you letter and let me know how Raider was. His was the only such letter I ever received. Steve Smith came from good stock and did not let down his country, his men, his father or I. What more can you say about a soldier?

So who were these men who seemed so different from others in the same army and division? Outsiders felt Charlie Company was lucky in the draw on personnel but this was laughable. Many, even within the company, claim it was because of me. This is in fact the biggest myth ever spun and led to the 'personality cult' comments. It was never about me or any other single leader in the unit. The singular driving force was the development of not a crew of 'grey men' but a true unit personality. They took care of and actually enjoyed the business of war but had their 'problem children' which were simply dealt with in-house and usually by the troops themselves.

These ranged from a fellow who decided he was a pacifist to a fellow we called later 'Admiral Rosenberg.' The pacifist decided he could not kill so I took his weapon and grenades away and gave him a D-handled shovel to carry, used for digging night positions in the rock-hard I Corps earth. After three days of fear and ridicule from the other troops he was no longer a pacifist and begged for his weaponry back. I gave it back and he voiced no more complaints about killing the enemy. If you sent an erring soldier to the rear he fell into a world geared to defend refusing to fight 'in a senseless war.’ You had to keep him beside you until one day he would morph into a hunter/soldier like the rest.

'Admiral Rosenberg' became a legend in the company for being sorry but also for being a unique character. He was a malingerer who would 'injure’ his back on a daily basis. Finally I left him grimacing in feigned pain on the trail. Once he realized he was left alone, he left his rucksack and ran to catch up. Then with a fire-team quietly observing I sent him back alone to retrieve his rucksack. I talked to him every day. He was intelligent and debated the right of the country to snatch him from a life of New York leisure simply because he partied rather than studied in school. Finally it became a joke between us but I vowed to keep him in the field and he began to come around as a soldier.

One day, I received a call from MAJ Klein, our battalion operations officer, who told me he would take all Jewish soldiers to Da Nang for religious services. He said I had one on the roster named Rosenberg. I said, 'No way - I will never get him back.' The Major assured me that he would maintain control and return the man to me in the field. I merely said, ‘I do not believe that.' They came and picked him up and Rosenberg gave me a sly grin as he flew away. 'You will not be back, you sly devil,’ I said to myself. The Major called and said he would personally see he got back to me in the field. 'He won't get away from me, Zippo.' I merely replied, 'Baloney.'

Three days later I received a radio call from the S-3: 'Zippo meet me secure in the green.' I merely replied: 'You lost him; he beat you.’ Major Kline replied with a chuckle, ‘Just meet me in the green.' After Chief cranked up the secure set and punched in the codes with his KY-38 punch key, I got the S-3. 'I lost him but it is a great story.' It seems that after the services the troops were told to have fun, rest and be ready to return to Evans. All, including the erring Rosenberg sang out a hearty 'Currahee sir'! All seemed well until the wee hours of the morning.

The Admiral in Da Nang lived in a lighted compound surrounded by troops, dogs and God knows what. He was awakened by noises in his kitchen and he rose, armed himself and crept into the kitchen and to the door of the pantry. Sitting there, wearing the Admiral's white mess jacket, medals and all, was a young man eating peaches from a number ten can and slopping juice down the jacket front. 'Who are you?’ inquired the Admiral. The lad answered, 'Who are you, I am Admiral Rosenberg.' The Admiral told him to sit tight and he would be back and then the doctors and corpsmen came to take this poor delusional soldier (who was smarted than all of them) gently away to the hospital. Rosenberg was fast moving from sorry soldier to the stuff of legend.

A short time later I got a post card from America. I do not know for sure who actually sent it but it came from the USA. It said simply: ‘Zippo, if I did war, I would want to do it with you but I don't do wars, so I came on home.‘ It was signed 'Admiral Rosenberg.’ I often wonder if the little shit has any problem being serviced by the VA. Probably not, he is much too smart for that.

Weaponry was an ongoing problem in trying to get you into a position to kill the enemy. We had the soldiers dressed in fatigues of various colors and camouflage patterns making it impossible for the enemy on the next ridge to judge who and what they were. Yet we were armed with the M-16A1/M203 and M-60 Machine Gun. After having two CAR-15 assault weapons shot out from my hands, I discarded this type weapon and went to using a captured AK folding stock assault weapon. I had been planning this since my request for a new barrel for the CAR I inherited from Reggie Moore went unheeded (The barrel was burned out and at over one hundred meters the ever increasing concentric circles made it impossible to hit the enemy). I wished to arm every point-man with the AK but the resistance within the command made this impossible. Only the Kit Carson Scouts and I carried the AK.

There was no understanding of the simple fact that success in combat is measured in seconds and not minutes. The enemy was much attuned to the difference in sounds of the weaponry (M-16/AK) being employed. If he heard an M-16 he went to ground and scurried away. I proved time and again if he was engaged by an AK held in the hands of an individual wearing a non-green mottled uniform, his little head popped up for that second needed to kill him.

If the enemy fired a B-40 we tried to answer with an M-72 LAW or two, along with our 40mm grenade launchers. This confused and scared him. We needed him confused and afraid.

We were selected to test the four-barreled rocket launcher called the FLAME, which fired White Phosphorous rounds. I saw the potential for using this weapon in conjunction with calling in air-strikes but the Air Force refused to cooperate. I wished to mark the forward and rear limits of an enemy column moving below the military crest of nearby ridges. I planned to do this with two WP rounds on each end. The idea would be to have the FAC off-set from the target and wait until he had fighters on station with 'Snake and Nape’ (CBU and Napalm) on board. This would allow him to line up his fighters before signaling his intentions by firing his own WP rockets. We would also fire M-72 LAWS and machine guns to distract the enemy from the incoming aircraft. The Air Force did not understand the war of seconds and not minutes.

Since the Air Force did not understand the concept, we coordinated with Squirrel and the Dragon gunships. The Army's gain and Air Force's loss. So close did our relationship become with the Dragon pilots and Squirrel that when I returned from R&R to Da Nang, the maintenance officer for Dragon flew me back to Evans and Currahee pad in the front seat of a Cobra. Very few, non-rated, Infantry officers can claim that distinction.

There was the unfortunate incident with Squirrel when I was returning to the field from a meeting at Evans. As I jumped from the OH-6 into a bomb crater, my rucksack caught the right-hand collective and I nearly crashed the little bird into the crater. That scared the crap out of Squirrel and me. I felt like a darned fool in front of a man who had supported us so well. We eventually sent the bulky 'FLAME" to the rear with my evaluation and never saw it again.

We used every weapon at the disposal of the US Army. We taped White Phosphorous (WP) grenades to the lower front of selected claymore mines and double-primed the combined device. This accomplished two things: (1) It marked your perimeter LP’s/ambushes for aircraft at night and (2) It terrorized the enemy because just a bit of WP hitting them became the 'gift that kept on giving.’ They either sat down or butchered it out of themselves or it burnt right through them. The only way they could make it stop burning was to cut off all air to it. This usually entailed them burying the burning body portion in the ground which made them much easier to catch. You could also tell when you hit an NVA with WP because he screamed for his mates to help him. Usually the disciplined little soldiers would lie when even terribly wounded. But nobody could shut up with old 'Wilson Pickett’ making its terrible course through him.

With our holes, ambushes/LP’s and our white fire belching claymores we were never attacked in a Night Defensive Position (NDP). There was one other reason for this. No man in Charlie Company was ever chewed out for throwing a grenade or busting a claymore if he detected enemy movement. Where ‘Mr. Claymore’ and ‘Mr. Grenade’ go, nothing grows. But this did cost us one good soldier. When checking positions at night I kept finding one soldier nodding off. I admonished, threatened and gave a swift kick or two to no avail.

We had a young Black Soldier who today would be diagnosed with a 'sleep disorder.' Time and again Remarks and I found him nodding off when we checked the perimeter at night. He tried everything from quietly humming to breathing exercises. I had just shaken him awake again and chastised him royally again. He felt terrible; ‘I am trying, Zip.’ I just told him to try harder and find in himself the solution and stay awake. It was the last time we would ever speak to him alive.

I assume he pulled the pin on a grenade and held it in his hand as a motivator to stay awake. He must have awakened when the grenade slipped from his fingers and fell into the hole as he sat on its rear edge. Knowing Remarks and I would know he had nodded off if, it exploded in his hole. He dove in after it but failed to find it within six seconds and my poor soldier died. The tough Remarks cried and whispered, ‘stupid’ to his lifeless body. I knew he had died trying to please his sergeant and me. But there is nothing gained by dwelling on such terrible things. You cannot get them back once they are gone and you can only try harder to preserve them. One thing is certain, if you go through the very army staff way of changing everything to show you have taken corrective action, you will lose more men. Mourn them, learn from the loss but do not build an uncertain attitude into your other men by making changes just to make an excuse for a terrible event.

[An aside about the Vietnamese airborne/ rangers:] I do not know them personally but the Vietnamese Airborne/Rangers were settled in the region and became involved in the shrimp trade. They bought boats and wives went to work in the canneries. They soon fell afoul of the KKK and labor unions. The Klan tried to attack their boats and unions tried to have the relatives intimidated and fired. The former Vietnamese Airborne/Rangers armed themselves and took on the Klan/unions at sea and as escorts for dependents (I joked with them that had they fought alongside of each other as well in the war, the result might have been different). I was sent there for three days and had a large meeting in a church where the Klan tried to declare, along with the unions, the unfairness of it all. I and a couple others ceased to be peacemakers and simply made it clear that the Airborne/Rangers were ready to fight in Vietnam and now on the Gulf of Mexico (The 11th Airborne Battalion came out virtually intact after defending Tan Son Nhut until the very end).

Most outstanding were members of the Airborne who came to the US virtually intact and tried to join the 82nd Airborne as a unit. They were denied and the rest is history. With this election victory all of us who stood beside the Vietnamese in battle can be intensely proud of them and frankly of ourselves. God Bless America.